Il Grande Gioco, morire per l’Afghanistan

19 Novembre 2021

di Stefano Olivari

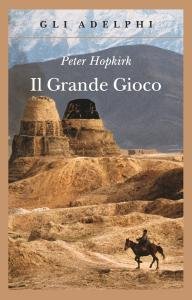

Cosa sappiamo dell’Afghanistan, al di là di qualche nome di città letto o ascoltato distrattamente negli ultimi decenni da spettatori, dall’invasione sovietica ai talebani al potere? Kabul, Kandahar, Herat, Jalalabad e poche altre località, prima di mettere mano a Google. Il Grande Gioco, lo straordinario libro di Peter Hopkirk, la cui lettura abbiamo rimandato per un trentennio, parte proprio dalla geografia per parlarci di una storia che spiega benissimo quella di oggi, anche se l’opera è uscita nel 1990 e l’argomento è la lotta diplomatica e paramilitare fra Inghilterra e Russia lunga tutto l’Ottocento, avente come obbiettivo il dominio commerciale nell’Asia Centrale e la difesa dei rispettivi imperi da parte dei reali britannici, la regina Vittoria su tutti, e dei vari zar.

Hopkirk dell’Asia ha scritto tantissimo, ma è ne Il Grande Gioco (The Great Game – On Secret Service in High Asia) che trova una formula diversa dagli aneddoti del giornalista e dal determinismo dello storico, incentrando la narrazione sugli uomini, con un’idea di base molto precisa: il corso della Storia è condizionato da alcuni personaggi eccezionali, non necessariamente grandi condottieri o primi ministri, anzi quasi mai, che provano a infrangere o a forzare le regole con obbiettivi vaghi ma sempre trascinati da un misto di coraggio, sete di conoscenza, avidità, brama di gloria e soprattutto inquietudine. Ogni capitolo ha un protagonista, inglese o russo, con il comune denominatore proprio dell’inquietudine: in quasi tutti i casi uomini con una facile carriera davanti, ma per un qualche oscuro motivo desiderosi di correre rischi incredibili in posti nemmeno segnati sulle mappe dell’epoca, con poca tutela da parte della madrepatria.

L’espressione Grande Gioco fu coniata da uno dei personaggi raccontati da Hopkirk, Arthur Conolly, la cui missione più importante fu quella di unire i tre canati del Turkestan (Chiva, Buchara e Kokand) per metterli sotto l’ombrello inglese in chiave anti-russa, ma sarebbe diventata famosa molti anni più tardi grazie a Rudyard Kipling e al suo Kim, uno dei nostri primi libri letti al di fuori degli obblighi scolastici: ad un primo livello proprio un’avventura per ragazzi con protagonista un ragazzo, in realtà un racconto degli anni finali del Grande Gioco, con tanto di spie, e sulle scelte che prima o poi ci si trova a dover fare. Anche nel libro di Hopkirk, peraltro equilibratissimo e per niente anti-russo, si respira a pieni polmoni la parte idealistica del colonialismo che c’è in Kipling, e che di recente ha messo Kim nel mirino della cancel culture. Fra l’altro nel Grande Gioco l’oggetto del desiderio finale è proprio l’India in cui cresce Kim, in una maniera quasi ossessiva.

Ma tornando alle 600 pagine di Il Grande Gioco che abbiamo da poco terminato e che ci hanno entusiasmato (come più volte detto, leggiamo e recensiamo solo i libri che ci piacciono, gli altri li abbandoniamo dopo due pagine in favore di Bologna-Salernitana), bisogna dire che il loro cuore non risiede nei disegni espansionistici di Regno Unito e Russia, ma nelle vicende umane di protagonisti, spesso eroi solitari o comunque lasciati soli: su tutti lo scozzese Alexander Burnes, le pagine sulla sua morte a Kabul sono fra le più forti del libro, l’inglese Charles Stoddart che sarebbe morto a Buchara insieme a Conolly (non togliamo alcuna suspense, quasi tutti protagonisti del Grande Gioco finiscono male e piuttosto giovani), l’irlandese Eldred Pottinger, l’eroe della difesa di Herat, e il russo Michail Cernjaev, il leone di Taskent.

Loro e gli altri pronti ad imprese militari impossibili o a incredibili operazioni di spionaggio in ambienti sospettosi e dispotici, in cui la durezza dell’Islam si saldava a quella di terre dove essere cattivi era obbligatorio. A colpire, con gli occhi di oggi, è come facessero a metà Ottocento a comunicare, raccogliere informazioni, ricevere e dare ordini, parlare con accento perfetto in più lingue.

Un grande libro, sicuramente non facile per chi detesta la geografia e la storia, ma affascinante in ogni sua riga. Conquista per l’attualità di ciò che suggerisce, cioè l’insensatezza di un controllo militare del territorio afgano e l’impossibilità, sia in Medio Oriente sia in Asia Centrale, di individuare l’interlocutore giusto e non soltanto per le divisioni tribali o le differenti idee di Islam. Ma conquista anche per lo spirito di avventura da romanzo che trasmette, davvero da brivido, superiore a quello di un viaggio su Marte nel 2021. Lo spirito di uomini che volevano fare la differenza e il cui sangue ha reso più grandi i loro paesi. Chi ha una storia così non può cedere sovranità, ma solo cercare un altro impero in forme più moderne, e pazienza se il cervello in fuga non concepisce che qualcuno abbia votato per la Brexit.

What do we know about Afghanistan, beyond a few city names read or listened to absent-mindedly over the past decades as spectators, from the Soviet invasion to the Taliban in power? Kabul, Kandahar, Herat, Jalalabad and a few other locations, before we got our hands on Google. The Great Game, the extraordinary book by Peter Hopkirk, takes geography as its starting point to tell us about a history that explains today’s very well, even though the work was published in 1990 and the subject is the diplomatic and paramilitary struggle between England and Russia throughout the nineteenth century, the aim of which was commercial domination in Central Asia and the defence of their respective empires by the British royal family, Queen Victoria above all, and the various tsars.

Hopkirk has written a great deal about Asia, but it is in The Great Game – On Secret Service in High Asia that he finds a formula that differs from the anecdotes of the journalist and the determinism of the historian, focusing the narrative on men, with a very precise basic idea: the course of History is conditioned by a few exceptional characters, not necessarily great leaders or prime ministers, in fact almost never, who try to break or force the rules with vague objectives but always driven by a mixture of courage, thirst for knowledge, greed, lust for glory and above all restlessness. Each chapter has a protagonist, English or Russian, with the common denominator of restlessness: in almost all cases men with an easy career ahead of them, but for some obscure reason eager to take incredible risks in places not even marked on the maps of the time, with little protection from the motherland.

The expression Great Game was coined by one of Hopkirk’s characters, Arthur Conolly, whose most important mission was to unite the three Turkestan canyons (Chiva, Buchara and Kokand) to bring them under the British umbrella in an anti-Russian key, but would become famous many years later thanks to Rudyard Kipling and his Kim, one of our first books read outside school obligations: at first level just a boy’s adventure starring a boy, in reality a tale of the final years of the Great Game, complete with spies, and about the choices one has to make sooner or later. Hopkirk’s book, which is very well balanced and not at all anti-Russian, is also full of Kipling’s idealistic colonialism, which has recently put Kim in the crosshairs of cancel culture. Among other things, in The Great Game the final object of desire is precisely the India where Kim grows up, in an almost obsessive way.

But going back to the 600 pages of The Great Game that we have just finished and that have thrilled us (as we have said many times, we read and review only the books we like, the others we abandon after two pages in favour of Bologna-Salernitana), it must be said that their heart does not lie in the expansionist designs of the United Kingdom and Russia, but in the human events of the protagonists, often lonely heroes or in any case left alone: above all the Scotsman Alexander Burnes, the pages on his death in Kabul are among the strongest in the book, the Englishman Charles Stoddart, who is said to have died in Buchara together with Conolly (let’s not take away any suspense, almost all protagonists of the Great Game end badly and rather young), the Irishman Eldred Pottinger, the hero of the defence of Herat, and the Russian Michail Cernjaev, the lion of Taskent.

They and the others were ready for impossible military feats or incredible espionage operations in suspicious and despotic environments, where the harshness of Islam was combined with that of lands where being bad was obligatory. What is striking, with today’s eyes, is how they managed in the mid-nineteenth century to communicate, gather information, receive and give orders, and speak with a perfect accent in several languages.

A great book, certainly not easy for those who detest geography and history, but fascinating in every line. It conquers because of the topicality of what it suggests, namely the senselessness of a military control of Afghan territory and the impossibility, both in the Middle East and in Central Asia, of finding the right interlocutor, and not only because of tribal divisions or different ideas of Islam. But it also conquers because of the novel-like spirit of adventure that it conveys, which is truly spine-chilling, superior to that of a trip to Mars in 2021. The spirit of men who wanted to make a difference and whose blood made their countries greater. Those with such a history cannot surrender sovereignty, only seek another empire in more modern forms, and patience if the brain on the run cannot conceive that someone voted for Brexit.

Translated with www.DeepL.com/Translator (free version)

Commenti Recenti