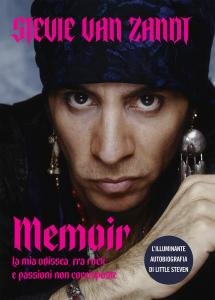

Memoir, l’odissea rock di Little Steven

In occasione dell’arrivo della sua autobiografia, abbiamo intervistato il consigliere di Bruce Springsteen. E abbiamo scoperto che di Steven Van Zandt non ne avremo mai abbastanza...

15 Ottobre 2021

di Simone Sacco

Si siede a mezzo metro da me e, come prima cosa, chiede alla sua addetta-stampa un caffè con l’aggiunta di latte. Parecchio latte. Lo sorseggia. Poi domanda di fare silenzio e mi fissa incuriosito. Forse perché anche io lo sto guardando in maniera insolita. Osservo stupito il viola, il tanto viola che si porta appresso (il foulard extra-large che gli arriva sino alle cosce più l’immancabile bandana), in sfregio alle scaramanzie dello showbusiness, come se fosse un fan di Prince epoca Purple Rain oppure un tifoso di Antognoni. E penso: “Mi piace”.

Little Steven (al secolo Steven Van Zandt, 71 splendidi anni il prossimo 22 novembre), di professione cantante/chitarrista, è quell’icona popolare che quasi tutti hanno approcciato, più o meno intensamente, nella propria vita: dai seriosi acquirenti anni Settanta dei dischi di Bruce Springsteen a chi lo vedeva come un vero agitatore politico negli anni Ottanta (il progetto U.A.A.A., United Artists Against Apartheid) passando per chi l’ha semplicemente adorato nei panni di Silvio Dante nel crime-drama de I Soprano o in quelli di Frank Tagliano in Lilyhammer, la più bella serie mafiosa attualmente disponibile su Netflix.

Ora “Miami” (come lo chiamavano/sfottevano i suoi vecchi amici del New Jersey a causa della sua insofferenza al freddo) ha messo tutto ciò in un intrigante libro di ricordi uscito da poco anche in Italia col titolo di Memoir: la mia odissea, tra rock e passioni non corrisposte. E noi, adesso, siamo qui per parlare con lui. “Dieci minuti, non uno di più”, ci avverte il management. Pazienza se al Boss (con Stevie al suo fianco) gliene occorsero quasi il doppio per suonare Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out nel suo meraviglioso doppio album Live in New York City uscito vent’anni fa, molti mesi prima della tragedia delle Twin Towers. Ok, faremo del nostro meglio.

Allora Stevie, da cosa cominciamo?

Dal fatto che ho scritto questo libro, ‘Unrequited Infatuations’, e che potrei stare qui a parlartene per dieci ore di fila! (ride). Anzi, fai così: tu intanto leggilo e dopo chiacchierare con me potrebbe anche essere irrilevante. Perché le cose che ho da dire stanno tra quelle pagine: non tutte, ma la gran parte sì.

Senti, facciamo un bel passo indietro. Tu, nel 1984, pubblichi Voice of America, il tuo secondo album solista dopo il bel debutto Men Without Women di due anni prima. A quel punto non facevi già più parte della E-Street Band e, particolare ancora più interessante, lo stesso Voice of America uscì esattamente quattro settimane prima (7 maggio 1984) di un certo Born In The U.S.A. (4 giugno)…

(ridacchia) Si è trattata di una scelta intelligente da parte mia, vero? Ok, nonostante io suoni su quel disco (le session di Born In The U.S.A., con Steven Van Zandt presente, partirono addirittura nel gennaio del 1982. Ndr) all’epoca non sapevo che Bruce gli avrebbe dato quelle fattezze. E ti sto parlando di quei colori sgargianti in copertina: il rosso, il bianco, il blu. Più le stelle e le strisce. Chi poteva immaginarselo? Anche il mio ‘Voice of America’ aveva un pizzico di bandiera americana a livello grafico però, dai, non scherziamo: quando uscì il suo album, il mio finì subito nel cestone delle offerte!

È per questo che stavolta sei stato più gentile e gli hai ceduto il passo? Il tuo memoir, d’altronde, esce cinque anni esatti dopo quello di Springsteen. Vale a dire il succoso Born To Run arrivato in libreria nell’autunno del 2016…

Mettiamola così: nel caso dei nostri rispettivi libri è stato meglio che sia uscito prima quello di Bruce così tutti quegli aneddoti che lui ha raccontato così bene in ‘Born To Run’, la gente non è più venuta a chiederli… a me! (ride) Altro fattore importante: ‘Unrequited Infatuations’, ci premo a sottolinearlo, non è affatto la postilla definitiva sulla vicenda di Bruce Springsteen & The E-Street Band, il suo capitolo mancante. Quello al massimo lo potranno essere i libri di Max Weinberg, Roy Bittan o Garry Tallent (rispettivamente batterista, tastierista e bassista del Boss. Ndr) se mai un giorno avranno voglia di scriverli.

Quindi questo tuo libro esattamente… cos’é?

È tante cose. Nel senso che racconto il mio ruolo al fianco di Springsteen – è quella è una bella parte della storia, ma non tutta la storia – eppure il volume, se ci pensi bene, non comincia con Bruce, ma con questo grintoso ragazzino del New Jersey completamente innamorato del rock ‘n’ roll. Poi arriva la seconda parte del memoir, quella dove la mia carriera prende il via, e qui la scrittura diventa un po’ simile a quella di un thriller alla Dan Brown. Nel senso che tu lettore non puoi smettere di leggere per scoprire cosa accadrà nel capitolo successivo. Anzi, a volte anche nella pagina successiva.

Negli anni Settanta e Ottanta hai compiuto tante imprese fantastiche, non sarò io di certo a ripetertele, e hai cominciato gli anni Novanta in maniera grandiosa partecipando al concerto di Wembley in onore della scarcerazione di Nelson Mandela (Nelson Mandela: An International Tribute for a Free South Africa andato in scena il 16 aprile 1990) dove hai suonato una memorabile versione di Sun City assieme a gran parte degli artisti presenti…

Sì, ricordo bene. Che giornata grandiosa fu quella!

Poi dopo, a parte la registrazione in studio di Murder Incorporated (con la E-Street Band riunita al gran completo) inclusa nel Greatest Hits di Springsteen della primavera ‘95, più niente da parte tua almeno fino al 1999. Quando un bel po’ di sorprese arrivarono tutte assieme: la messa in onda de I Soprano, i nuovi tour della riconciliazione col Boss, il tuo nuovo album (ampiamente sottovalutato) Born Again Savage. In pratica perché gli anni Novanta furono così evanescenti per te?

Prima di tutto lascia che ti ringrazi per aver citato ‘Born Again Savage’, un disco a mio avviso bellissimo e a cui tengo molto. Gli anni Novanta? Col tempo sono arrivato a considerarli nella mia testa una specie di decennio sprecato (“lost decade”). Sai, allora e per la prima volta nella mia vita mi sono trovato senza un vero obbiettivo da perseguire. Prima invece era sempre una costante ricerca di quello che sarebbe successo dopo. In parole povere ero nel bel mezzo degli anni Novanta, con cinque album a nome mio alle spalle (‘Men Without Women’, ‘Voice of America’, ‘Freedom – No Compromise’, ‘Revolution’ più il progetto United Artists Against Apartheid che generò ‘Sun City’) e con una carriera solista che non mi aveva portato da nessuna parte. Sono cose che ti fanno riflettere, no?

Come ne sei venuto fuori?

Continuando a lavorare in gran segreto. Quando mi sono guardato indietro per raccogliere idee per il libro – bang – ho scoperto di aver fatto un mucchio di cose anche negli anni Novanta! Scatoloni interi di progetti che non avevo mai reso pubblici. Nastri pieni di bella musica inedita. E così, ancor prima del successo de ‘I Soprano’ e delle tante tournée mondiali con Bruce, mi sono accorto che in un decennio assolutamente privo di piani, be’, mi ero dato eccome da fare… (sorride)

Torniamo un attimo a Sun City e al suo video diretto da Jonathan Demme, il compianto regista de Il Silenzio degli Innocenti. Quello che si apre con Miles Davis che spara accordi dissonanti nella sua tromba. Messaggio politico a parte, la consideri una delle canzoni rock-soul più travolgenti di ogni epoca?

Vero: l’unione di rock e soul è uno dei marchi di fabbrica della mia storia. Sono stato completamente soddisfatto dell’intera esperienza legata a ‘Sun City’, un po’ perché mi ha fatto conoscere tanti grandi artisti tra cui Ringo Starr (il primo Beatle che ho incontrato di persona in vita mia e che suona la batteria nel brano in questione), un po’ perché quello era il momento di fare qualcosa di aggressivo, con parole forti che scuotessero le coscienze. Voglio dire: eravamo a metà degli anni Ottanta e nessuno negli Stati Uniti sapeva che cazzo fosse l’apartheid! Non esisteva uno straccio di movimento di protesta e serviva che la nazione venisse informata della situazione in Sud Africa. Dovevo tirarmi su le maniche. E penso di esserci riuscito.

21 novembre 1987, un sabato sera. Tu eri in Italia, a Roma. Ricordi quella notte?

L’incontro con Adriano? Sì, lo cito anche nel mio libro. (sorride)

Esatto. Andasti ospite con la tua band, in quella leggendaria edizione di Fantastico condotta da Adriano Celentano, ad eseguire Bitter Fruit. Hai mai più rivisto il Molleggiato in questi ultimi 34 anni?

Purtroppo no, ma porto ancora nel cuore quella performance. L’hanno ritrasmessa recentemente sulla tv italiana? No? Pazienza, tanto su YouTube il filmato originale si trova facilmente. Comunque con Adriano volevo organizzare qualcosa – una cena, un rapido incontro – durante questi miei giorni a Milano dove ho presentato il libro. Mi hanno detto che aveva altri impegni; ed io ho un aereo che mi attende per riportarmi a casa.

Visto che prima ti ho citato Bitter Fruit, cosa ne pensi della cover che ne ha fatto in italiano Antonello Venditti tramutandola nel 1995 in Prendilo Tu Questo Frutto Amaro? La tua era una canzone rock politica, la sua più una satira pop sulla politica italiana…

L’importante è che non abbia cambiato granché le parole. (mi guarda un po’ dubbioso. Ndr). Sai, difficilmente quei versi avrebbero avuto senso in italiano, quindi mi ha fatto piacere la cosa, ma ad essere sincero non me ne sono occupato granché.

Nel 2017 ti sei esibito alla Rondhouse di Londra con i tuoi Disciples Of Soul. E ad un certo punto ti è venuto a trovare Paul McCartney per eseguire I Saw Her Standing There dei Beatles…

Non poteva essere che quella! ‘I Saw Her Standing There’ è stata la prima in assoluto. Il primo 45 giri che ho comprato in vita mia. E se suono la chitarra per campare lo devo esclusivamente a quella canzone dei Fab Four.

Quella sera hai pensato almeno per un secondo “Hey, sto suonando sul palco con McCartney! Lo stesso Paul che, da ragazzino, ho visto ospite da Ed Sullivan il 9 febbraio 1964”…?

Se è per questo, i Beatles li ho visti dal vivo pure allo Shea Stadium in quel famoso ferragosto del 1965. (sorride) In ogni caso, no. Non ho mai visto Paul McCartney come un mito, ma al massimo come un collega e un amico. E questo discorso potrei fartelo anche per Richie Sambora, Peter Wolf, David Byrne ecc. Tutta gente che è venuta a trovarmi su qualche palco dei miei vari tour. Tutte persone normali. Esattamente come me e te.

During the promotion of his autobiography, we met Bruce Springsteen’s advisor. And we discovered that we can never have enough of Steven Van Zandt…

By Simone Sacco

He sits down two feet away from me and, first thing, asks his press secretary for a coffee with milk added. Lots of milk. He sips it. Then he asks for silence and stares at me curiously. Perhaps because I am also looking at him in an unusual way. I stare in amazement at the purple, so much purple that he wears (the extra-large scarf that reaches his thighs plus the ever-present bandana), in defiance of the superstitions of show business, as if he were a fan of Prince’s Purple Rain era or a fan of Giancarlo Antognoni. And I think, “I like it.”

Little Steven (born Steven Van Zandt, 71 years old next November 22), singer/guitarist by profession, is a popular icon that almost everyone has approached, more or less intensely, in their lives: from Springsteen’s serious ‘70s buyers to those who saw him as a real political agitator in the ‘80s (the U.A.A.A. project, United Artists Against Apartheid) through to those who simply adored him as Silvio Dante in the crime-drama The Sopranos or as Frank Tagliano in Lilyhammer, the finest mafia series currently available on Netflix.

Now “Miami” (as his old friends in New Jersey used to call him/screw him because of his intolerance to the cold) has put all this into an intriguing book of memories recently published under the title of Unrequited Infatuations. And we, now, are here to talk to him. “10 minutes, not one more”, warns the management. No matter if it took the Boss (with Stevie at his side) almost twice as long to play Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out in his wonderful double album Live in New York Cityreleased twenty years ago, many months before the Twin Towers tragedy. Okay, we’ll do our best.

So Stevie, what should we start with?

With the fact that I wrote this book, ‘Unrequited Infatuations’, and that I could stand here and talk to you about it for ten hours straight! (laughs) In fact, tell you what: you read it in the meantime, and afterwards, chatting with me might as well be irrelevant. Because the things I have to say are between those pages: not all of them, but most of them are.

Look, let’s take a big step back. In 1984, you released Voice of America, your second solo album after the fine debut Men Without Women two years earlier. By that time you were no longer part of the E-Street Band, and, even more interestingly, Voice of America was released exactly four weeks earlier (May 7, 1984) than Born In The U.S.A. (June 4)…

(chuckles) That was a smart choice on my part, wasn’t it? Ok, although I play on that record (the sessions of Born In The U.S.A., with Steven Van Zandt on guitar, started in January 1982. Ed.) at that time I didn’t know that Bruce would have given him those features. And I’m talking about those garish colors on the cover: red, white, blue. Plus the stars and stripes. Who could have imagined that? Even my ‘Voice of America’ had a hint of the American flag on the graphic level, but, come on, let’s not joke: when his album came out, mine immediately ended up in the bargain bin!

Is that why you were kinder this time and gave him a pass? Your memoir, on the other hand, comes out exactly five years after Springsteen’s, namely the juicy Born To Run that arrived in bookstores in the fall of 2016…

Let me put it this way: in the case of our respective books, it was better that Bruce’s came out first so that all those anecdotes that he told so well in ‘Born To Run’, people didn’t come asking for them anymore… to me! (laughs) Another important factor: ‘Unrequited Infatuations’, I’d like to stress, is by no means the definitive postilla on the story of Bruce Springsteen & The E-Street Band. Its missing chapter. At the most, it could be a book by Max Weinberg, Roy Bittan or Garry Tallent (respectively drummer, keyboardist and bassist of the Boss. Ed.) if they ever want to write them.

So this book of yours, exactly what is it?

It’s a lot of things. I mean – in those pages I tell the story of my role alongside Springsteen – and that’s a great part of the story, but not the whole story – yet the book begins with this feisty kid from New Jersey completely in love with rock ‘n’ roll. Then comes the second part of the memoir, the part where my career takes off, and here the writing becomes a bit like a Dan Brown thriller. In the sense that you the reader can’t stop reading to find out what will happen in the next chapter. In fact, sometimes even on the next page.

In the ‘70s and ‘80s you performed many fantastic feats, I certainly won’t repeat them to you, and you started the ‘90s in a great way by participating in the Wembley concert in honor of Nelson Mandela’s release from prison (Nelson Mandela: An International Tribute for a Free South Africa staged on April 16, 1990) where you played a memorable version of Sun City along with most of the artists present…

Yes, I remember well. What a great day that was!

Then after that, apart from the studio recording of Murder Incorporated (with the E-Street Band reunited) included in Springsteen’s Greatest Hits of spring ’95, nothing more from you until 1999. When quite a few surprises came all at once: the airing of The Sopranos, the new reconciliation tours with the Boss, your new (vastly underrated) album Born Again Savage. So my question is – basically why were the ‘90s so evanescent for you?

First of all let me thank you for mentioning ‘Born Again Savage’, a record that I think is beautiful and that I cherish. The ‘90s? With time I came to consider them in my head a lost decade. You know, then for the first time in my life I found myself without an objective to pursue. Before instead it was always a constant search for what would happen next. Simply put, I was in the middle of the 90’s, with five albums behind me (‘Men Without Women’, ‘Voice of America’, ‘Freedom – No Compromise’, ‘Revolution’ plus the United Artists Against Apartheid project that spawned ‘Sun City’ single) and a solo career that had gotten me nowhere. These are things that make you think, right?

How did you come out of it?

By continuing to work in secrecy. When I looked back to gather ideas for the book – bang – I discovered I had done a bunch of stuff in the 90s! Whole boxes of projects I’d never made public. Tapes full of beautiful unreleased music. And so, even before the success of ‘The Sopranos’ and the world tours with Bruce, I realized that in a decade with absolutely no plans, well, I had been busy as hell… (he smiles)

Let’s go back to Sun City and its video directed by Jonathan Demme, the late director of Silence of the Lambs. The one that opens with Miles Davis firing dissonant chords into his trumpet. Political message aside, do you consider it one of the most overwhelming rock-soul songs of any era?

True: the combination of rock and soul is one of the trademarks of my history. I was completely satisfied with the whole ‘Sun City’ experience, partly because it introduced me to Ringo Starr (the first Beatle I ever met in person who plays drums on the song), and partly because it was the time to do something aggressive, with strong words that would shake people’s consciences. I mean, it was the mid-80s and nobody in the US knew what the fuck apartheid was! There wasn’t a shred of a protest movement and the nation needed to be informed about the situation in South Africa. I had to roll up my sleeves. And I think I succeeded.

November 21, 1987, a Saturday night. You were in Italy, in Rome. Do you remember that night?

The meeting with Adriano? Yes, I even mention it in my book… (smiles)

That’s right. You went as a guest with your band, in that legendary edition of Fantastico saturday night show hosted by Adriano Celentano, to perform Bitter Fruit. Have you ever seen him again in the last 34 years?

Unfortunately not, but I still carry that performance in my heart. Has it been rebroadcast recently on Italian TV? No? It’s all right, you can easily find the clip on YouTube. Anyway, I wanted to organize something with Adriano – a dinner, a quick meeting – during my days in Milan where I presented the book. They told me he had other commitments, and I have a plane waiting to take me home.

Since I mentioned Bitter Fruit earlier, what do you think of Antonello Venditti’s cover of it in Italian, turning it into Prendilo Tu Questo Frutto Amaro? Yours was a political rock song, his is more of a pop satire on Italian politics…

The important thing is that he didn’t change the words too much. (he looks at me a bit doubtful. Ed.) You know, those verses would have hardly made sense in Italian, so I was pleased about that, but to be honest I didn’t take much care of it.

In 2017 you performed at London’s Rondhouse with your Disciples Of Soul. And at one point you were visited by Paul McCartney to perform The Beatles’ I Saw Her Standing There…

It could only be that one! ‘I Saw Her Standing There’ was the first one ever. The first 7-inch I ever bought in my life. And if I play guitar for a living I owe it solely to that Fab Four song.

Did you think for at least a second, “Hey, I’m playing on stage with McCartney! The same Paul that, as a kid, I saw as a guest on Ed Sullivan on February 9, 1964”…?

If that’s the case, I saw the Beatles live at Shea Stadium on that famous August bank holiday in 1965… (he smiles)Anyway, no. I have never seen Paul McCartney as a myth, but at most as a colleague and a friend. I could say the same thing about Richie Sambora, Peter Wolf, David Byrne, etc. All people who came to see me on some stage of my various tours. All normal people. Exactly like you and me.

Commenti Recenti