Le battute su Inghilterra-Germania

L'ottavo più nobile di Euro 2020 è il primo scontro diretto nell'era del politicamente corretto, che accomuna sfottò e guerra vera...

29 Giugno 2021

di Roberto Gotta

Inghilterra-Germania, dunque. Ancora. Oddio, in competizioni ufficiali si sono incontrate 10 volte dalla finale mondiale del 1966 in poi, un paio di queste in sfide di andata e ritorno, quindi non siamo a livelli dell’ormai annuale PSG-Bayern o simili, ma considerando che in questi 55 anni gli inglesi hanno partecipato a 33 tra qualificazioni e fasi finali di Europei o Mondiali si tratta di una percentuale non alta: un confronto diretto ogni 3,3 manifestazioni. Poi ci sono le amichevoli e i torneucci (Azteca Tournament, US Cup), ma quelli non tornano utili al racconto.

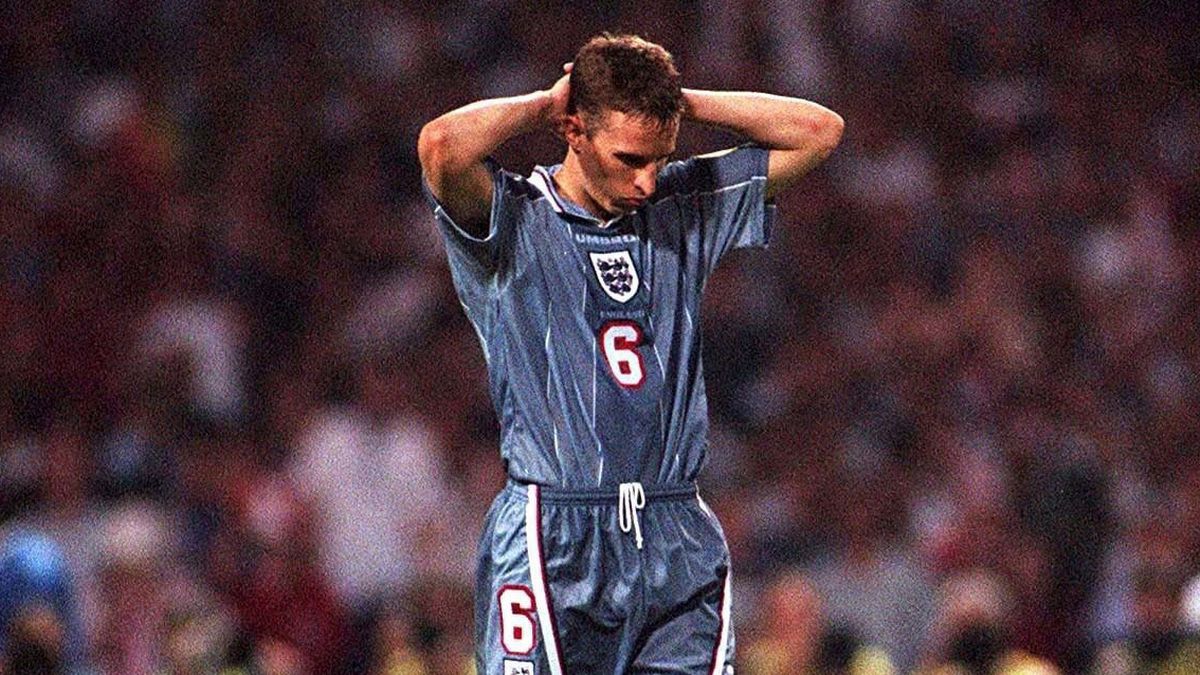

Che è quello, da parte inglese, di sconfitte in serie negli appuntamenti decisivi, quattro su quattro: quarti di finali dei Mondiali 1970, semifinali dei Mondiali 1990, ottavi di finale dei Mondiali 2010. Agli Europei, la semifinale del 1996. Rigori nel 1990, quelli al Delle Alpi con gli errori di Stuart Pearce e Chris Waddle, e nel 1996 a Wembley, con l’errore decisivo di Gareth Southgate, l’attuale Ct. Negli altri due casi la sfida è arrivata nella fase a gironi: 0-0 nell’apertura del gironcino a tre, comprendente anche la Spagna, dei Mondiali 1982, dal quale i tedeschi poi passarono alla semifinale vinta ai rigori contro la Francia e infine alla finale persa contro l’Italia, e 1-0 Inghilterra in quello, tradizionale, di Euro 2000, nel quale però vennero eliminate entrambe subito, a vantaggio di Portogallo e Romania.

Insomma, un disastro, solo marginalmente equilibrato da successi come il 5-1 all’Olympiastadion di Monaco nelle qualificazioni ai Mondiali del 2002, partita di ritorno dell’1-0 con cui i tedeschi avevano ‘chiuso’, il 7 ottobre del 2000, il vecchio Wembley, in una giornata grigia che fu seguita dalle dimissioni del Ct Kevin Keegan. Convinto, con l’onestà per lo meno pubblica che lo ha sempre contraddistinto, di non aver più nulla da dare alla squadra, per la quale era più un motivatore e un ispiratore che un tattico.

Naturalmente nel computo delle partite a esito secco manca la prima dell’era moderna, il 4-2 inglese nella finale dei Mondiali del 1966, quando ancora la Germania era Germania Ovest. Il 3-2 era stato segnato da Geoff Hurst ed è il famoso gol (o più probabilmente non gol, visto il rimbalzo della palla sul filo della linea di porta) sul quale ora, con la tecnologia moderna, non ci sarebbero dubbi. Serve a poco ricordare che ingiustizia palese – e non incerta come all’epoca – venne invece fatta agli inglesi nell’ottavo di finale dei Mondiali 2010, quando sul 2-1 tedesco un tiro da lontano di Frank Lampard colpì l’interno della traversa e rimbalzò decisamente e vistosamente dentro la porta. Niente 2-2, finì 4-1 per la Germania con l’ennesima occasione persa dalla cosiddetta Golden Generation inglese, anche se nello specifico di quella generazione erano rimasti solo lo stesso Lampard, Ashley Cole, John Terry, Steven Gerrard – sistemato all’ala – e Wayne Rooney, con Fabio Capello in panchina.

La sesta sfida ad eliminazione diretta arriva per la terza volta a Wembley: tra vecchio e nuovo stadio, è dal 1975 che l’Inghilterra non ci batte i tedeschi, ma sono dati di cui non si ricorda nessuno e che obiettivamente servono a poco. Perché Inghilterra-Germania è soprattutto una questione di cuore, di emozioni, di sentimenti, anche di stereotipi. A senso unico, o quasi: come avete già letto nell’articolo del mese scorso su Thomas Tuchel, la relazione tra le due nazioni, o meglio tra le due fazioni, è enigmatica, apparentemente facile da leggere ma con una serie notevole di angoli nascosti, in cui giacciono verità scomode.

La prima, ovviamente, è quella relativa all’origine tedesca della Casa Reale britannica, che nel 1917 da Sassonia-Coburgo-Gotha passò a chiamarsi Windsor per decisione di Re Giorgio V, convinto dalla fortissima animosità anti-tedesca causata dallo scoppio della Prima Guerra Mondiale. Decisione che causò ironie in giro e risentimento nel ramo tedesco, ad esempio in Guglielmo II, ultimo imperatore di Germania e di Prussia, che era peraltro nemico in guerra ma pure… cugino di Giorgio V. Roba che è in tutti i libri di storia, peraltro.

Al tifoso di oggi però delle parentele lontane nel tempo frega molto poco. C’è da battere la Germania, e conta solo quello. Perché il punto è questo: per il tifoso inglese medio i tedeschi sono i nemici per antonomasia, più ancora degli scozzesi, mentre a parti invertite non c’è medesimo sentimento di rivalsa continua. Sempre disegnando a grandi tratti, il tedesco gode di più a battere l’Olanda, un po’ meno l’Austria, magari la Francia, l’Italia e la Spagna perché superarle vuol dire, in genere, puntare a grandi traguardi.

Degli inglesi interessa per reazione, non per azione voluta: visto che loro ci tengono così tanto, li accontentiamo. Ecco perché giocatori come Gosens non si sono tenuti dentro il desiderio di vincere a Wembley: di fronte alla propaganda e alle esagerazioni i moderati sono i primi a perdere la pazienza. La propaganda può essere il tormentone It’s Coming Home, di cui si è già parlato, ma anche l’incessante ripetizione di riferimenti bellici, anche questi già illustrati nell’articolo su Tuchel. Quasi sempre volutamente grotteschi, una sorta di pantomima a mezzo stampa, di buoni contro cattivi caricaturali sul palcoscenico della scuola: perché anche se è vero che qualche imbecille che traduce le parole in scazzottate c’è sempre, è anche vero che l’inglese medio non ‘odia’ il tedesco medio, semmai lo trova strano, differente, ci scherza sopra, così come fa con lo scozzese, l’italiano, lo spagnolo.

Dire, dello scozzese etichettato come tirchio, che un tizio di Aberdeen, trovata per terra una stampella, è tornato a casa e ha rotto una gamba alla moglie, pur di poterla utilizzare, non dovrebbe essere offensivo, in un mondo normale: sarebbe uno sfottò, in inglese ‘banter’, così come lo sono stati i tanti segnali di esultanza italiana all’eliminazione della Francia dagli Europei. L’odio vero è un’altra cosa, fortunatamente rara, anche se ormai da alcuni anni la parola viene strumentalizzata per campagne politiche che ne sviliscono e volgarizzano il senso: guarda caso, per traduzione banale e frettolosa dall’inglese ‘hate’, a demonizzare chi non gradisce il tuo vestito rosso perché preferisce il blu e immediatamente diventa ‘rossofobo’.

Lettura, quella leggera e sdrammatizzante, purtroppo sconosciuta a chi, ad esempio gli autori del libro The Ingerland Factor, ha esaminato decenni di tifo inglese, etichettando come xenofobi e razzisti slogan e atteggiamenti che erano semplicemente espressione di sfottò, anche pesanti. Tanto che spesso i destinatari delle presunte offese l’hanno presa sul ridere, o nemmeno ci hanno fatto caso. Come i tedeschi, appunto: alcuni hanno sollevato obiezioni di fronte a certe esagerazioni, alcuni altri magari, meno civili, hanno cercato lo scontro, ma per il resto si tratta di una pantomima natalizia estesa per tutto l’anno, costruita su elementi ormai scomparsi.

Se i britannici/inglesi infatti parlano ancora della Seconda Guerra Mondiale o addirittura della prima («Se per caso domani i tedeschi ci battessero nello sport che abbiamo inventato ci consoleremo pensando che noi li abbiamo sconfitti in quello che hanno inventato loro», cioé la guerra, scrisse un editorialista prima della finale dei Mondiali del 1966), è evidente che nel Regno Unito di oggi, in cui una minoranza politicamente corretta impone la propria volontà alla maggioranza, l’elemento-coraggio, la capacità della gente di resistere ad un nemico vero – non quello sportivo né quello inventato dalla propaganda buonista – è venuto meno rispetto ad un tempo. È celebre la frase di un anonimo londinese, udita su un autobus pochi giorni dopo la disfatta di Dunkerque, quella ‘gloriosa sconfitta’ nella quale i britannici, inseguiti dai tedeschi fin sulle coste francesi, riuscirono comunque a portare in salvo oltre 300.000 soldati: «Se non altro li sfideremo in finale, e giocheremo in casa». L’umorismo nero di chi ha paura ma non lo vuole dimostrare: messe al sicuro le truppe, sarebbero presto arrivati gli aerei dell’aviazione tedesca ma – appunto – avrebbero dovuto sorvolare l’isola, giocando in trasferta.

Quella sì che era una cosa seria, lì sì sparavi a vista o correvi disperato temendo che ti cadesse una bomba in testa: una nostra parente, durante il bombardamento alleato di Alessandria dell’aprile 1944, perse un’amica che era tornata indietro a prendere un quaderno e rimase sotto le macerie della propria casa, colpita proprio in quel momento e ricordiamo raggelati il racconto, che spiega la differenza tra la guerra e le scaramucce verbali da stadio, una recita che anche nei suoi lati meno eleganti è fatta di parole, gesti, bandiere e poco altro, checché ne dicano i benpensanti privi di umorismo.

Questa sera – già che siamo in argomento – potrebbe ad esempio risuonare Ten German Bombers, celebre canto che racconta l’abbattimento progressivo (si parte da «C’erano dieci bombardieri tedeschi» e si finisce «Non era più nessun bombardiere tedesco») di una spedizione aerea e sul quale la Uefa ha già ammonito gli inglesi: parole che certo non possono suonare dolci ai discendenti di chi in un bombardamento morì, ma che ovviamente non riflettono alcun odio reale.

E questa mattina la BBC, durante la trasmissione Breakfast, ha mandato in onda una mini-banda che eseguiva la colonna sonora di La grande fuga, il film del 1963 che racconta l’evasione di un gruppo di soldati da un campo di prigionia in Polonia. Se una cosa del genere la fa la BBC, sprofondata da anni in un politicamente corretto oltre l’imbarazzante, è chiaro che alla base non c’è alcun tipo di animosità reale ma solamente la vestizione con paramenti sacri in vista di una partita che – dal lato inglese – tali abbigliamenti richiede quasi in automatico. Il tifoso britannico, nella media, è del resto quello che urla qualcosa di spregiudicato e poi si fa una risata con gli amici intorno: se non è un buzzurro o un nostalgico hooligan, non resta minuti interi a urlare con gli occhi iniettati di sangue, e anche quando canta slogan rischiosi non ci crede – forse – nemmeno lui.

Inghilterra-Germania è dunque uno scontro curioso, con un’animosità a senso unico che si espande di volta in volta, di episodio in episodio, ma più leggera di quel che sembri a chi non sa ridere di nulla e vede odio dappertutto. Via dagli stadi i violenti e chiunque insulti il diverso – di pelle, tifo, orientamento sessuale – ma gli sfottò bisogna tollerarli, altrimenti non è più Inghilterra-Germania ma una partita tra squadre, troppo spesso, di livello differente.

England-Germany, then. Again. They have met 10 times in official competitions since the 1966 World Cup final, a couple of them in return matches, so we are not at the level of the now annual PSG-Bayern or similar, but considering that in these 55 years the English have participated in 33 European or World Cup qualifiers and finals, it is not a high percentage: a direct confrontation every 3.3 events. Then there are the friendly matches and tournaments (Azteca Tournament, US Cup), but these are not useful for the story.

The story is one of serial defeats in decisive matches, four out of four: the quarter-finals of the 1970 World Cup, the semi-finals of the 1990 World Cup and the round of 16 of the 2010 World Cup. At the European Championships, the 1996 semi-final. Penalty kicks in 1990, those at the Delle Alpi with the errors of Stuart Pearce and Chris Waddle, and in 1996 at Wembley, with the decisive error of Gareth Southgate, the current coach. In the other two instances the challenge came in the group stage: 0-0 in the opening three-way group, which also included Spain, of the 1982 World Cup, from which the Germans went on to win the semi-final on penalties against France and then the final, which they lost to Italy, and 1-0 to England in the traditional Euro 2000 group stage, in which, however, they were both eliminated immediately, to the benefit of Portugal and Romania.

In short, a disaster, only marginally balanced by successes such as the 5-1 win at the Olympiastadion in Munich in the 2002 World Cup qualifiers, the return match of the 1-0 win with which the Germans had ‘closed’ the old Wembley on 7 October 2000, on a grey day that was followed by the resignation of coach Kevin Keegan. Convinced, with the at least public honesty that has always distinguished him, that he had nothing more to give to the team, for which he was more of a motivator and an inspiration than a tactician.

Of course, missing from the tally of outright matches is the first of the modern era, England’s 4-2 victory in the 1966 World Cup final, when Germany was still West Germany. The 3-2 score was scored by Geoff Hurst and is the famous goal (or more likely non-goal, given the bounce of the ball off the goal line) about which now, with modern technology, there would be no doubt. There is little point in remembering that a clear injustice – and not an uncertain one as it was at the time – was done to the English in the round of 16 of the 2010 World Cup, when at 2-1 Germany hit the inside of the crossbar and Frank Lampard’s shot from distance bounced noticeably into the goal. No 2-2, it ended 4-1 to Germany with yet another missed opportunity for England’s so-called Golden Generation, although specifically of that generation only Lampard himself, Ashley Cole, John Terry, Steven Gerrard – placed on the wing – and Wayne Rooney remained, with Fabio Capello on the bench.

The sixth knockout match comes to Wembley for the third time: between the old and new stadiums, it is since 1975 that England have not beaten the Germans, but these are figures that no one remembers and that objectively serve little purpose. Because England-Germany is above all a question of heart, of emotions, of feelings, even of stereotypes. One-way, or almost: as you have already read in last month’s article on Thomas Tuchel, the relationship between the two nations, or rather between the two factions, is enigmatic, apparently easy to read but with a considerable number of hidden corners, in which lie uncomfortable truths.

The first, of course, is the German origin of the British Royal House, which in 1917 changed its name from Saxe-Coburg-Gotha to Windsor by decision of King George V, convinced by the strong anti-German animosity caused by the outbreak of the First World War. This decision caused irony and resentment in the German branch, for example in Wilhelm II, the last emperor of Germany and Prussia, who was an enemy in the war but also a cousin of George V. Stuff that is in all the history books, by the way.

However, today’s fans don’t care about distant relations. We have to beat Germany, and that’s all that matters. Because here is the point: for the average English fan, the Germans are the enemies par excellence, even more so than the Scots, while on the other hand there is not the same feeling of continuous revenge. Still drawing in broad strokes, the German enjoys beating Holland more, Austria a little less, perhaps France, Italy and Spain because overcoming them generally means aiming for big goals.

The English are interested by reaction, not by intentional action: since they care so much, we satisfy them. That’s why players like Gosens didn’t keep their desire to win at Wembley inside: when faced with propaganda and exaggeration, moderates are the first to lose patience. Propaganda can be the catchphrase It’s Coming Home, which has already been discussed, but also the incessant repetition of war references, also illustrated in the article on Tuchel. Almost always deliberately grotesque, a sort of pantomime in the press, of caricatured good guys versus bad guys on the school stage: because even if it is true that some imbecile who translates words into fisticuffs is always there, it is also true that the average Englishman does not ‘hate’ the average German, if anything he finds it strange, different, he jokes about it, just as he does with the Scotsman, Italian and Spanish.

To say, of the Scotsman labelled as cheap, that a guy from Aberdeen, having found a crutch on the ground, went home and broke his wife’s leg, just to be able to use it, should not be offensive, in a normal world: it would be a joke, in English ‘banter’, as were the many signs of Italian jubilation at France’s elimination from the European Championships. True hatred is something else, fortunately rare, even if for some years now the word has been exploited for political campaigns that debase and vulgarize its meaning: it happens to be a banal and hasty translation from the English ‘hate’, to demonize those who do not like your red dress because they prefer blue and immediately become ‘red-phobic’.

A light and downplaying reading, unfortunately unknown to those who, for example the authors of the book The Ingerland Factor, have examined decades of English football fans, labelling as xenophobic and racist slogans and attitudes that were simply the expression of mockery, even heavy. So much so that the recipients of the alleged offence often laughed it off, or didn’t even notice. Like the Germans: some objected to certain exaggerations, some others, perhaps less civilised, sought confrontation, but otherwise it was a year-round Christmas pantomime, built on elements that have now disappeared.

Indeed, if the British/English are still talking about the Second World War or even the first (‘If by chance tomorrow the Germans beat us in the sport we invented, we will console ourselves with the thought that we beat them in what they invented’, i.e. war, wrote one columnist before the 1966 World Cup final), it is clear that in today’s United Kingdom, where a politically correct minority imposes its will on the majority, the element of courage, the ability of people to resist a real enemy – not the sporting one nor the one invented by feel-good propaganda – is less than it used to be. The phrase of an anonymous Londoner, heard on a bus a few days after the defeat at Dunkirk, that ‘glorious defeat’ in which the British, pursued by the Germans all the way to the French coast, managed to save more than 300,000 soldiers, is famous: ‘At least we will challenge them in the final, and we will play at home’. The black humour of those who are afraid but don’t want to show it: once the troops were safe, the German air force planes would soon arrive but – precisely – they would have to fly over the island, playing away.

That was a serious matter, you could shoot on sight or run desperately fearing that a bomb would fall on your head: A relative of ours, during the Allied bombardment of Alexandria in April 1944, lost a friend who had gone back to get a notebook and was left under the rubble of her own house, which was hit at that very moment, and we remember the story chillingly, which explains the difference between war and the verbal skirmishes of the stadium, a play that even in its less elegant aspects is made up of words, gestures, flags and little else, whatever the humourless right-thinkers may say.

Tonight – while we’re on the subject – we might, for example, hear Ten German Bombers, the famous song that recounts the gradual shooting down (starting with ‘There were ten German bombers’ and ending with ‘There were no more German bombers’) of an air expedition and about which Uefa has already warned the English: words that certainly cannot sound sweet to the descendants of those who died in a bombing raid, but which obviously do not reflect any real hatred.

And this morning the BBC, during its Breakfast programme, aired a mini-band playing the soundtrack of The Great Escape, the 1963 film about the escape of a group of soldiers from a prison camp in Poland. If the BBC, which for years has been plunged into embarrassing political correctness, does something like this, it is clear that there is no real animosity behind it, but only the dressing up in sacred vestments for a match which – on the English side – almost automatically requires such attire. The average British fan is also the one who shouts something unconventional and then has a laugh with his friends around him: if he is not a boorish or nostalgic hooligan, he does not stay for minutes screaming with bloodshot eyes, and even when he chants risky slogans he does not – maybe – believe it either.

England-Germany is therefore a curious clash, with a one-way animosity that expands from time to time, from episode to episode, but lighter than it seems to those who cannot laugh at anything and see hatred everywhere. Away from the stadiums the violent and anyone who insults the different – of skin, fan, sexual orientation – but the teasing must be tolerated, otherwise it is no longer England-Germany but a game between teams, too often, of different level.

Commenti Recenti